Update (25 May 2022): While I mentioned it in passing, this essay doesn’t really cover the Haven for the Human Amoeba community very much, which is a shame, because it was an important part of early ace history. Unforunately, at the time I originally researched and wrote this, Yahoo Groups had been shut down and the HHA archive was lost media.

However, since then, with help from Sennkestra and Phoenix the II, the archive is back! You can browse it here on Ace Archive. Hopefully in the future I will make a followup post talking more about that community specifically. I’ve also updated many of the other links in this essay to link to Ace Archive, where many of the images and document scans have been transcribed.

The asexual community as we know it today is quite young; while the broader LGBTQ rights movement is usually traced back to the Stonewall Riots of 1969, the modern asexual community evolved much later. The founding of the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN) in 2001 was an important milestone in the asexual movement; the organization was the first to make serious inroads promoting public awareness of asexuality and spawned one of the first large, cohesive online communities for aces. One of the most significant impacts the AVEN community has had is establishing and standardizing the language of asexuality, including the term “asexual.” Before AVEN, people who would come to identify as asexual went by various names, and there was not a common understanding of what asexuality meant. Today, the organization’s website defines “asexual” as “a person who does not experience sexual attraction” in a banner at the top of the page; it’s the first thing you see when you visit the website, and the importance of this definition can’t be overstated in terms of how it allowed many fractured and disparate communities to come together under a single banner.

Understanding how important it was for the ace community to standardize the language of asexuality raises the question of what this language looked like before AVEN. In this essay, I want to trace the history of the term “asexual” and the terms which preceded it, and I want to take a look at how asexuality has been defined over the decades and how we came to our modern understanding of it. This account will focus heavily on academic literature from the 19th and 20th centuries and how they incorporated asexuality into their typologies of human sexuality. We’ll also take a look at the first asexual activists and asexual communities which emerged in the early years of the LGBTQ rights movement. We’ll continue chronologically from the first mentions of asexuality in academic literature up until the founding of AVEN in 2001. Finally, we’ll analyze some of the trends which emerged over the history of asexuality.

In 1869, Karl-Maria Kertbeny authored two pamphlets protesting Prussian sodomy laws. In these writings, he famously coins the terms heterosexual and homosexual. Less well-known is that he also coined the term monosexual to refer to people who exclusively masturbate. While this isn’t quite how we define asexuality today, Kertbeny helped pioneer the idea that sexuality is an innate quality rather than a choice, and this makes his writings one if the first cases where something resembling asexuality is both recognized as a sexual orientation and given a name.

Richard von Krafft-Ebing writes about asexuality in his 1886 work Psychopathia Sexualis (Psychopathy of Sex). In it, he uses the term anesthesia sexual to refer to people with an “absence of sexual feeling.” He provides several case studies of people who he believes fit this description, explaining, “These functionally sexless individuals are rare cases, and, indeed, always persons having degenerative defects, in whom other functional cerebral disturbances, states of psychical degeneration, and even anatomical signs of degeneration, may be observed.” The cases described in Krafft-Ebing’s work describe people who clearly seem to be asexual by our modern definition, but most of these cases don’t mention anything of the “defects” or “degeneration” that Krafft-Ebing insists they experience. This is likely one of the first examples of the pathologization of asexual people which continues to this day.

Another early attempt at creating a sexual typology which includes asexuality came from German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld. Hirschfeld is known for founding the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee in 1897, which was the first LGBTQ rights organization in history and campaigned against the legal persecution of sexual and gender minorities. Later, he would go on to found the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute of Sex Research) in 1919, which advocated for sex education, contraception, treatment of STDs, and the emancipation of women. The Institute offered marriage and sex counseling, gender-affirming endocrinologic and surgical services for transgender patients, and “transvestite passes” which allowed transgender people to present in public without facing legal persecution. Among this long list of accomplishments, Hirschfeld also published the pamphlet Sappho und Sokrates in 1896, which recognizes people without any sexual desire under the label “anesthesia sexual”—the same term used by Krafft-Ebing. In this work, Hirschfeld also develops a quantitative scale for describing human sexuality which rates the intensity of same-sex and opposite-sex attraction on separate axes, each from 1 to 10. Many sexologists would attempt to create scales for rating human sexuality, but this is the first I was able to find which explicitly accounts for asexuality.

German sexologist Emma Trosse not only gave us a definition of asexuality, but was openly asexual herself. Trosse was the first woman to publish a scientific work on homosexuality in women and advocated for legal protections for sexual minorities. In her 1897 work Ein Weib? Psychologisch-biographische: Studie über eine Konträrsexuelle (A woman? Psychological-biographical study of a contrary-sexual), she gives us a definition of asexuality under the label Sinnlichkeitslosigkeit (asensuality) and says in a footnote, “Author has the courage to admit to this category.”

One of the earliest uses of the term “asexual” in literature I found comes from Otto Weininger’s misogynist diatribe Sex and Character. In it, Weininger denigrates women for sexually tempting men, asserting confidently that it is not possible for a woman to be asexual, going as far as to say, “And it is clear that if only one single female creature were really asexual, or could be shown to have a real relationship to the idea of personal moral worth, everything that I have said about woman, its general value as psychically characteristic of the sex, would be irretrievably demolished, and the whole position which this book has taken up would be shattered at one blow.”

In 1916, 1918, and 1920, Hirschfeld published Sexualpathologie Teil I–III (Sexual Pathology Part I–III). In these later works, he uses the terms asexual and anerotic to refer to people with no sexual drive and speculates about what could cause people to be this way. He considers that it could be a case of sublimation—where people are too devoted to their hobby or occupation to devote time or energy to sex, exposure to anti-erotic literature, or low levels of sex hormones. While this is the first usage of the term “asexual” to refer to human sexuality I was able to find in scientific literature, Hirschfeld’s analysis is incredibly pathologizing and does not recognize asexuality as a sexual orientation in the same way we do today. Hirschfeld also coins the term automonosexual to refer to people who are sexually attracted to themselves. Unlike later works which would make a distinction in their typology between asexual people with a libido and those without, Hirschfeld seems to use this term specifically to refer to people who are sexually excited by their own body, even going as far as to compare one patient to Narcissus from Greek mythology. Hirschfeld talks at length about automonosexualism in his transgender patients—his thoughts on this topic seem to mirror those of Ray Blanchard, who would later coin the term autogynephilia to describe a similar phenomenon1.

Another early usage of the term “asexual” comes from the 1933 work The Sexual Urge: How It Grows or Wanes by Charles Samson Féré. However, this usage of the term does not refer to a lack of libido or sexual attraction, but instead to non-sexual motivations for jealousy in interpersonal relationships. An example of this is the jealousy a child might feel when a parent’s attention is focused elsewhere. Féré writes, “The asexual nature of jealousy-psychosis shoes itself in particular when it has regard to persons who have nothing to do with sexual competition, e.g., the parents of those who excite the jealousy.”

In another attempt to come up with a scientific explanation for asexuality, Clifford Allen writes in his 1940 work The Sexual Perversions and Abnormalities about asexuality as a form of sublimation. Unlike Hirschfeld’s theory about sublimation, Allen posits that asexuality is a defense mechanism employed by people with “abnormal” sexual preferences (such as homosexuality or paraphilias) in order to avoid those desires and replace them with non-sexual ones. He writes, “By sublimation we mean the more or less conscious inhibition of the abnormal instinctual object with the substitution of an asexual object.” This problematic attitude towards asexuality persists to this day with the common myths that aces are “homosexuals in denial” or secretly pedophiles.

A more recognizable scientific work recognizing asexuality comes from American biologist and sexologist Alfred Kinsey. Widely considered the father of the sexual revolution in the US, Kinsey is most well-known for publishing the Kinsey Reports in 1948 and 1953. In these works, he argues that humans cannot be exclusively categorized as heterosexual or homosexual, and develops a scale to rate human sexuality on a range from 0, meaning “exclusively heterosexual,” to 6, meaning “exclusively homosexual.” The scale also included an additional “X” classification for people with “no socio-sexual contacts or reactions.” This report gives us some of the first demographic data on the prevalence of asexuality, with 1.5% of adult male subjects and 19% of adult female subjects falling into the “X” category. It’s important to note, however, that the Kinsey Scale was based on sexual experiences and not sexual attraction or self-identity. This means his scale cannot distinguish between people who lack sexual attraction and allosexual people who just lack sexual experience. Additionally, the Kinsey Scale is a one-dimensional scale, which is a step backwards in terms of accounting for asexual people when compared to the scale developed by Hirschfeld in Sappho und Sokrates.

In the Kinsey Reports, Kinsey does not use the term “asexual” to refer to people who fall into his “X” classification. Instead, in males2, Kinsey talks about “apathy” towards sex, describing such individual as “low in sex drive.” Unlike Hirschfeld, Kinsey does not attempt to speculate on the causes of asexuality, stating, “Whether the factors are biologic, psychologic, or social, it is certain that such persons exist.” Kinsey also rejects the idea that asexuality is a form of sublimation, stating, “But such inactivity is no more sublimation of sex drive than blindness or deafness or other perceptive defects are sublimation of those capacities.” Kinsey also takes a stance against the notion that asexuality is a condition requiring treatment, saying, “Considerable psychiatric therapy can be wasted on persons (especially females) who are misjudged to be cases of repression when, in actuality, at least some of them never were equipped to respond erotically.” While Kinsey somewhat misses the mark in defining asexuality, his work does make strides in countering the pathologization of asexuals in scientific literature.

One of the first appearances of the term “asexual” in literature outside of scientific publications comes from Anton Szandor LaVey’s 1969 work The Satanic Bible. Modern Satanism is an ideological movement which uses Satan as a metaphor to promote personal autonomy, rationality, and pragmatic skepticism3. Satanists are nontheistic, and don’t actually believe in Satan. Rather, they reappropriate Satanic imagery from Christian theology to promote causes like egalitarianism, social justice, and separation of church and state. LaVey writes, “Satanism condones any type of sexual activity which properly satisfies your individual desires—be it heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, or even asexual, if you choose.” In line with other Satanist thinkers, LaVey’s attitudes toward sexuality were remarkably progressive for the time. However, his understanding of asexuality is still incomplete. He also writes:

Asexuals are invariably sexually sublimated by their jobs or hobbies. All the energy and driving interest which would normally be devoted to sexual activity is channelled into other pastimes or into their chosen occupations. If a person favors other interests over sexual activity, it is his right, and no one is justified in condemning him for it. However, the person should at least recognize the fact that this is a sexual sublimation.

Like Hirschfeld, LaVey frames asexuality as a choice borne out of being too caught up with one’s hobbies and occupation to focus on sex. While this work is one of the first to use the term “asexual” in a positive—or at least neutral—tone instead of as a pathology or a pejorative, he fails to recognize that one can lack sexual attraction.

In 1972, The Asexual Manifesto was written by Lisa Orlando and published by the New York Radical Feminists4. In this work, Orlando gives us a clear definition of asexuality through a feminist lens, describing it as “relating sexually to no one.” While Orlando doesn’t use the language of “sexual attraction” standardized by the AVEN community, her work is one of the first to acknowledge a distinction between libido and a desire to have sex with others; she explains, “if one has sexual feelings they do not require another person for their expression.” Orlando is clear that asexuals can still desire nonsexual physical affection and intimacy and rejects the common notion that sexual relationships are the only way to achieve them. This is somewhat indicative of how later asexuals would differentiate between sexual and sensual attraction.

The Asexual Manifesto is clearly a product of the feminism of the 1970s5; Orlando frames asexuality as a form of protest against the patriarchal norm that women exist for the sexual gratification of men, and she devotes significant portions of it to talking about the sexual objectification of women. However, she does point out that her caucus chose to reject the label “anti-sexual,” as they wanted to avoid the connotation that sexuality is “degrading or somehow inherently bad.” Unlike our modern understanding of asexuality as a sexual orientation, Orlando’s Manifesto frames asexuality as a choice, and an inherently political one at that. Overall, this work is notable for being one of the first pieces of literature written by asexuals for the purpose of defining asexuality.

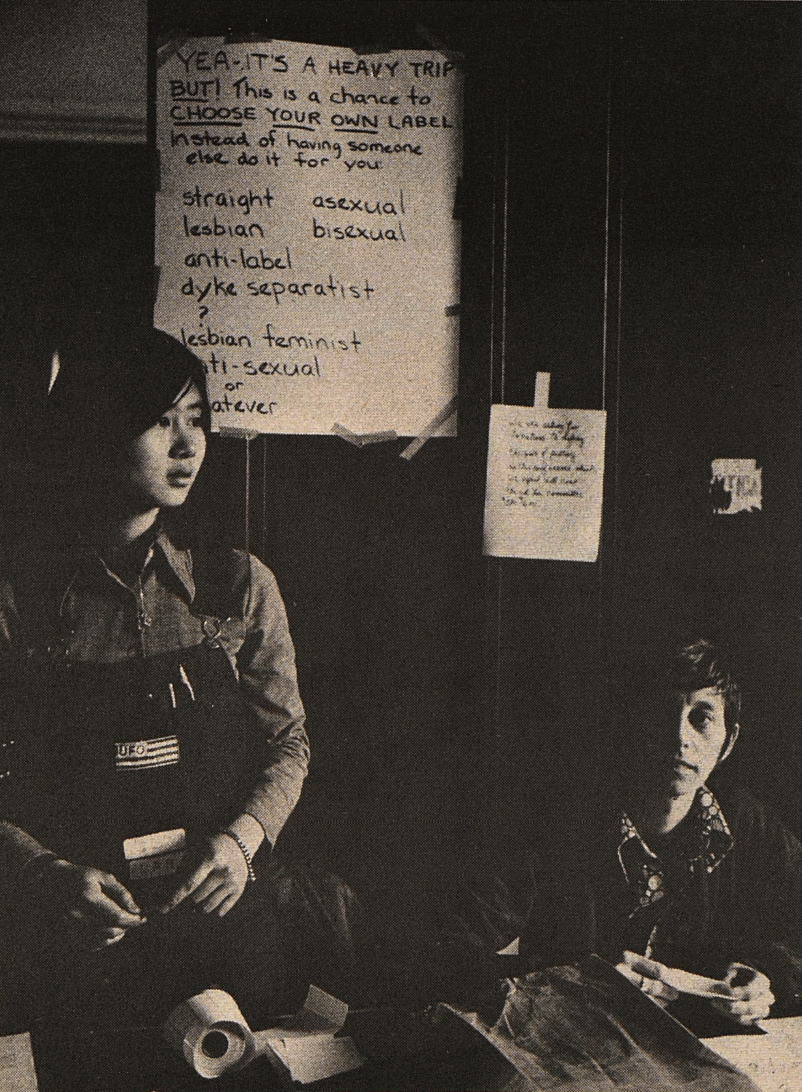

Lisa Orlando’s The Asexual Manifesto was referenced in the January 1973 issue of the feminist news journal Off Our Backs, where the author mentions attending a workshop on asexuality led by Barbara Getz—another member of the asexuality caucus of the New York Radical Feminists. The article summarizes asexuality as, “an orientation that regards a partner as nonessential to sex, and sex as nonessential to a satisfying relationship.” The next issue of Off Our Backs included a photo of activists at Barnard College with a sign that reads, “This is a chance to choose your own label instead of having someone else do it for you.” followed by a list of labels including “asexual.”

You can find a full transcript of the image and accompanying article here.

Myra Johnson wrote one of the first academic papers about asexuality in 1977, which was published as part of the book The Sexually Oppressed. In the paper, Johnson distinguishes between people who are asexual and people who are autoerotic. The former group consists of people who have no libido, while the latter group consists of people who have a libido but have no desire to have sex with others. The fact that she makes this distinction in her typology is interesting, because while there is discourse about libido in the modern asexual community—which has spawned microlabels like autochorisexual and aegosexual—aces today generally define asexuality by attraction alone, and the modern language of “sexual attraction” is absent in her writing. Still, her paper is one of the first to call attention to the systemic social oppression that asexual people face. She mentions how asexual people are oppressed by their invisibility and the general consensus that they don’t exist, and she talks about how asexuality is commonly construed as being either a religious obligation or a psychological problem, with no room for people who don’t feel sexual desire. Additionally, she is critical of the feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s—particularly how the sexual revolution fails asexual and autoerotic women by glorifying the importance of sexual availability and sexual desire. While this paper’s typology and terminology still differs from that which the asexual community would eventually settle on, she is one of the first to bring attention to the social issues asexual people face—issues which are still relevant today.

In 1979, sexologist Michael Storms published a study creating a new scale for describing human sexuality. The Erotic Response and Orientation Scale aims to explicitly include asexuality by mapping human sexuality on two axes instead of the one axis used by the Kinsey Scale. The purpose of this scale was to address the Kinsey Scale’s inability to distinguish between asexuality and bisexuality. While this scale was a step in the right direction in terms of accounting for asexuality, it still does not account for aces who differentiate between different types of attraction; many of the criteria used to place respondents on the scale refer to what some aces would classify as sensual or romantic attraction rather than sexual attraction.

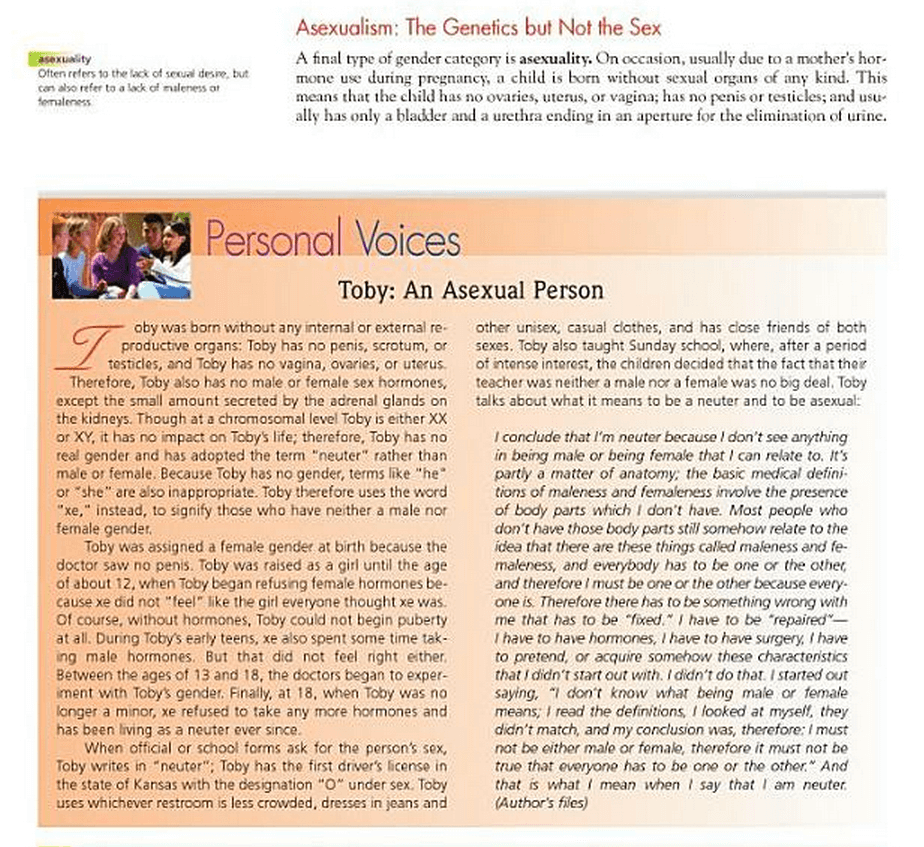

While at this point in history the use of the term “asexual” to refer to a sexual orientation was starting to become more common, that doesn’t mean there wasn’t significant confusion surrounding the term. In 1989, American talk show host Sally Jesse Raphael interviewed autism rights activist Jim Sinclair under the alias Toby. Jim is intersex, a self-described neuter6 person, and asexual7. This interview was the first time most audience members had been introduced to these concepts, and it made such a profound impact that many people confused being intersex, being neuter, and being asexual for years after. In literature, the term asexual was often used to refer to Jim’s anatomy instead of intersex. An example of this is the 2004 book, Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity.

You can find a full transcript of the article here.

In another example of scientific literature which gave credibility to the term “asexual”, Anthony Bogaert published a study on the prevalence of asexuality in 2004 in The Journal of Sex Research. In this study, Bogaert defines asexuality as “the state of having no sexual attraction for either sex,” which is remarkably similar to the definition used by the AVEN community. Bogaert also contrasts asexuality with sexual aversion disorder and hypoactive sexual desire disorder8, making this an early example of a study on asexuality which does not pathologize it. A major leap that this study makes over previous research, such as the Kinsey Reports, is specifically defining asexuality as the lack of sexual attraction and not a lack of sexual behavior or self-identification as asexual. As a result, this study was the first to give us a reliable estimate of the prevalence of asexuality without including allosexual people who lack sexual experience or excluding asexual people who have never heard the term before. Bogaert’s study concludes that approximately 1% of people are asexual, which is a statistic that is still cited in ace communities to this day.

At this point, some of the first online communities dedicated to asexuality have started to emerge. In 1997, Zoe O’Reilly published a blog post titled “My life as an amoeba”. In the post, O’Reilly describes herself as asexual and talks about her experience coming out to friends and family. While the term “asexual” was in more common use at this point, this is the first instance of the term “amoeba” being used as a tongue-in-cheek label for asexual people, which was popular in the late 1990s and early 2000s. After this, in 2000, a Yahoo group for asexuals called the Haven for the Human Amoeba was formed. This group was organized as a single email thread, and this structure quickly became unwieldy as the community grew. The need for an online community of asexuals with support for threaded discussions was quickly becoming apparent.

Finally, in 2001, AVEN was founded by David Jay with the goals of promoting public acceptance of asexuality and facilitating the growth of an asexual community. Without a doubt, the organization has been the first to make serious progress towards achieving those two goals.

The language of asexuality has a complicated history, and this account is by no means exhaustive. Asexuality has gone by many different names and been defined in many different ways over the decades, and it took until the early 21st century for consensus among the community to emerge. Looking back over the history of asexuality, a few general conclusions can be made. First, asexuality was “discovered” and named independently several times by scientists and activists going back to at least the mid 19th century, and it took until at least the mid-to-late 20th century for the term “asexual” to become the predominant label. Second, many of the people to first talk about asexuality, especially in academic literature, were not themselves asexual. Third, asexuality has been defined in many different ways over the decades; while some historical definitions of asexuality do approximate the commonly understood definition we use today, others have defined it as a lack of libido, a lack of sexual experience, a lack of time and energy to devote to sex, a psychological defense mechanism, and even a political ideology. Fourth, for much of the history of sexology, asexuality has been pathologized in scientific literature, with many scientists attempting to devise scientific explanations for its causes.

All of this raises the question of why asexuality took so long to be understood and develop a community when compared to other sexual and gender minorities. Of course, the LGBTQ movement as a whole has had to fight tooth and nail to develop a community and gain public recognition, but those things came later for asexuals than for most other people in the community. Is the issue one of demographics—that there aren’t as many of us? Or is the story of asexuality a testament to how deeply rooted allonormativity is in our society? Whatever the case, with how quickly the ace community has grown in recent years, only good things can come.

-

Autogynephilia is a now-discredited theory which attempts to explain sexuality in transgender women. His findings have been rejected by the WPATH as lacking empirical evidence. ↩︎

-

The Kinsey Reports consist of two works: “Sexual Behavior in the Human Male” and “Sexual Behavior in the Human Female.” As a result, Kinsey analyzes the sexuality of men and women separately. ↩︎

-

For an example of a contemporary Satanist organization, see The Satanic Temple. ↩︎

-

For more background on the context behind The Asexual Manifesto and Lisa Orlando, see this blog post by Siggy where he interviews Orlando. ↩︎

-

For more background information on the history of asexuality and celibacy in early radical feminism, see this blog post by Siggy. ↩︎

-

Jim uses the term “neuter” to describe xir gender identity and expression in much the same way the term “non-binary” is used today. ↩︎

-

Jim doesn’t use the term “asexual” in the interview, but xe does describe xirself as asexual in an essay xe wrote titled “Personal Definitions of Sexuality”. ↩︎

-

The DSM-5 would later clarify that this disorder does not apply to asexual people. ↩︎